|

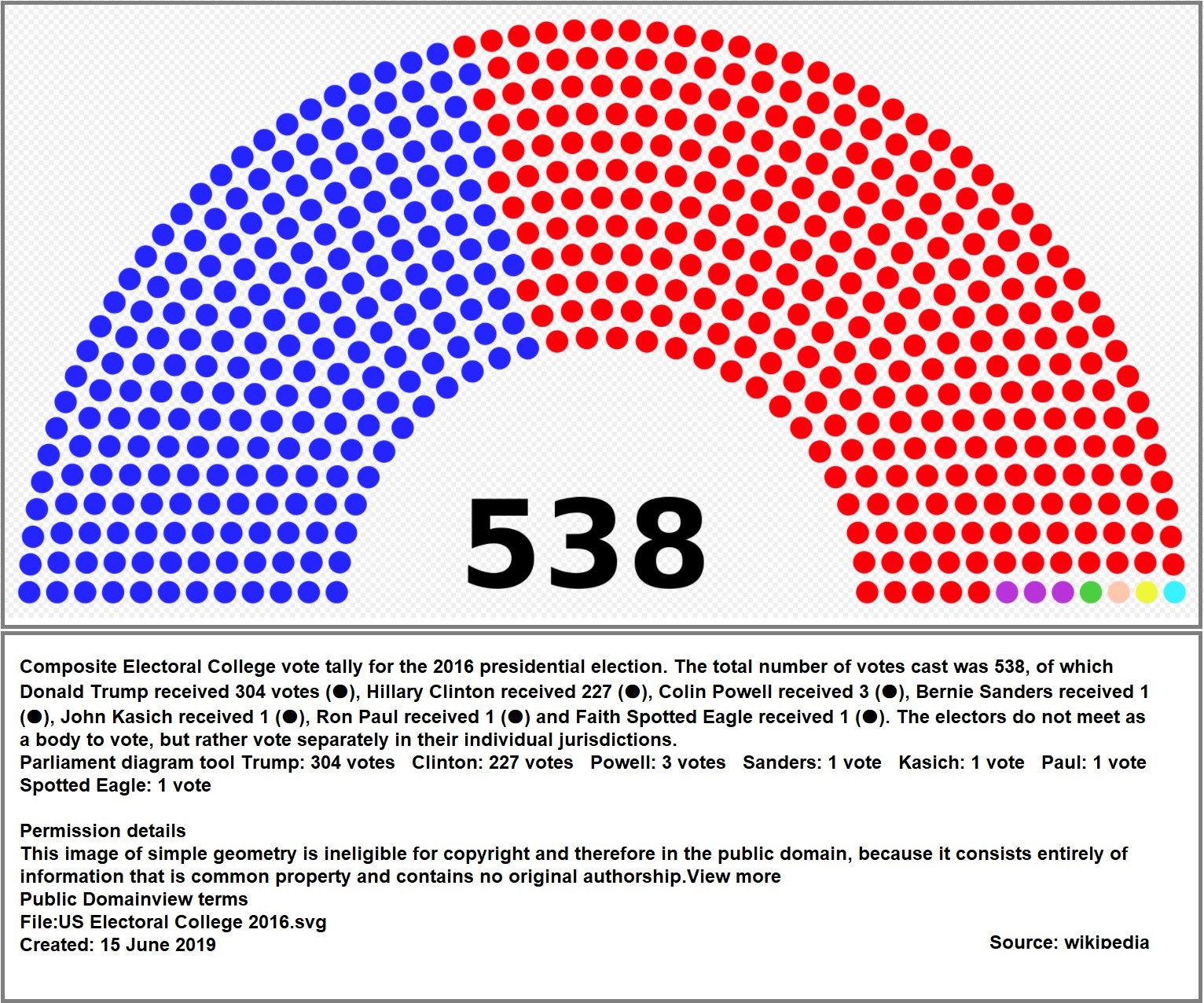

The Electoral College in United States of America refers to the group of presidential electors required by the United States Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of electing the president and vice president of the United States. Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution provides that each state shall “appoint” electors selected in a manner its legislature determines, and it disqualifies any person holding a federal office, either elected or appointed, from being an elector. There are currently 538 electors, and an absolute majority of electoral votes, 270 or more, is required to win the election.

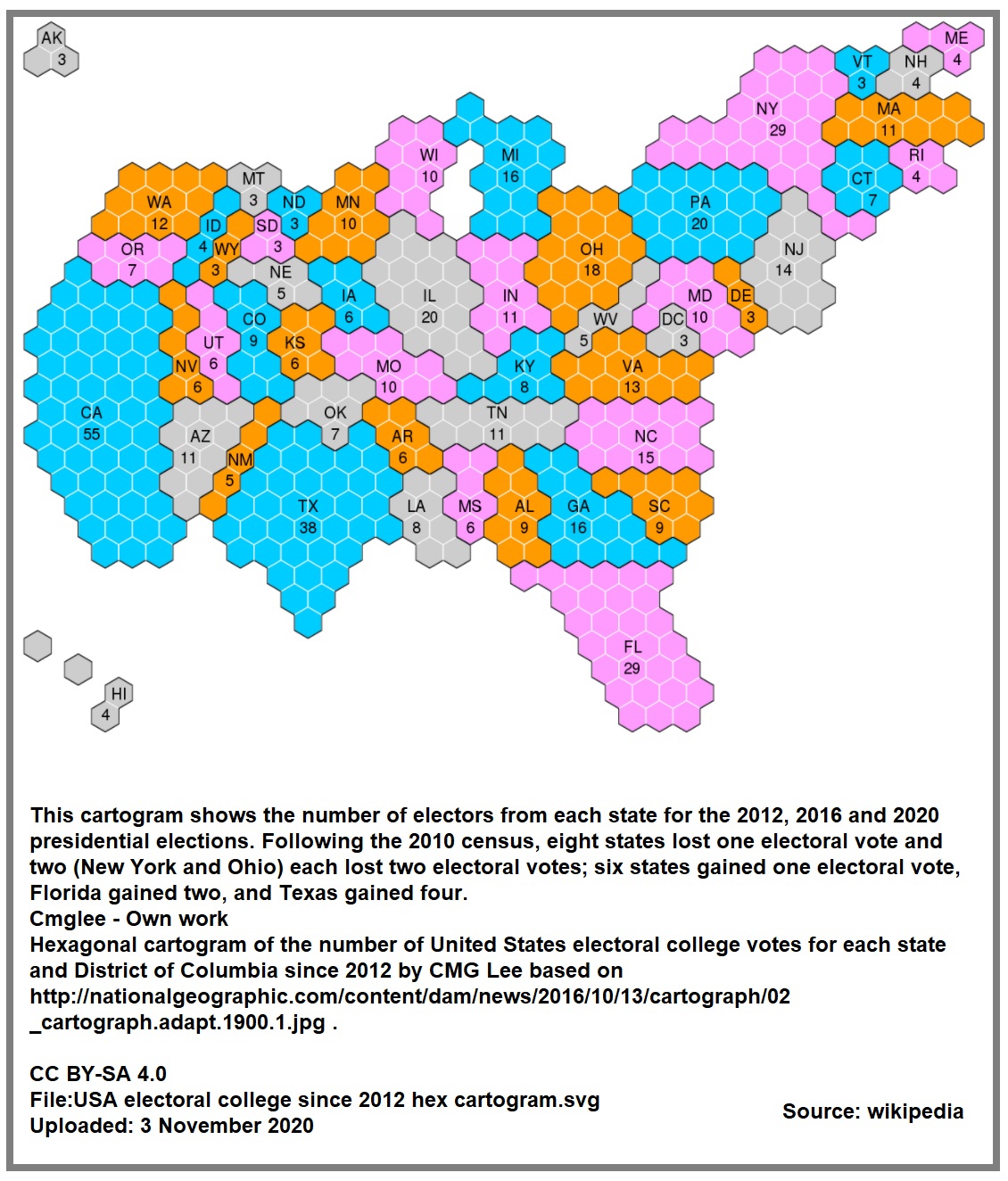

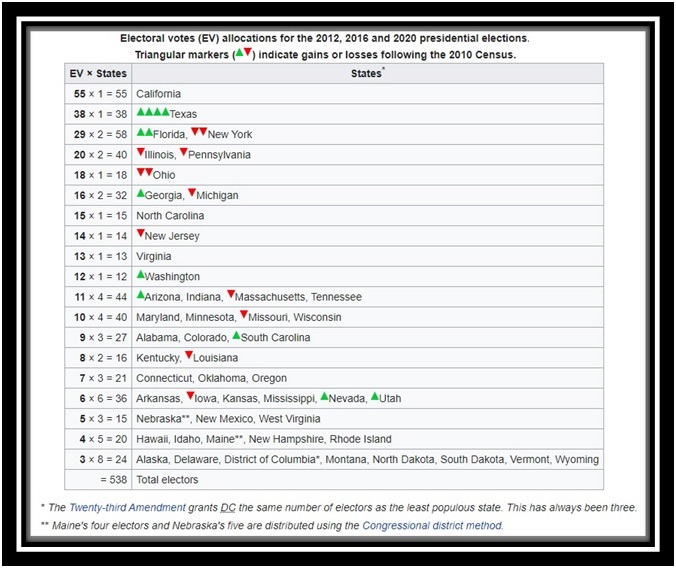

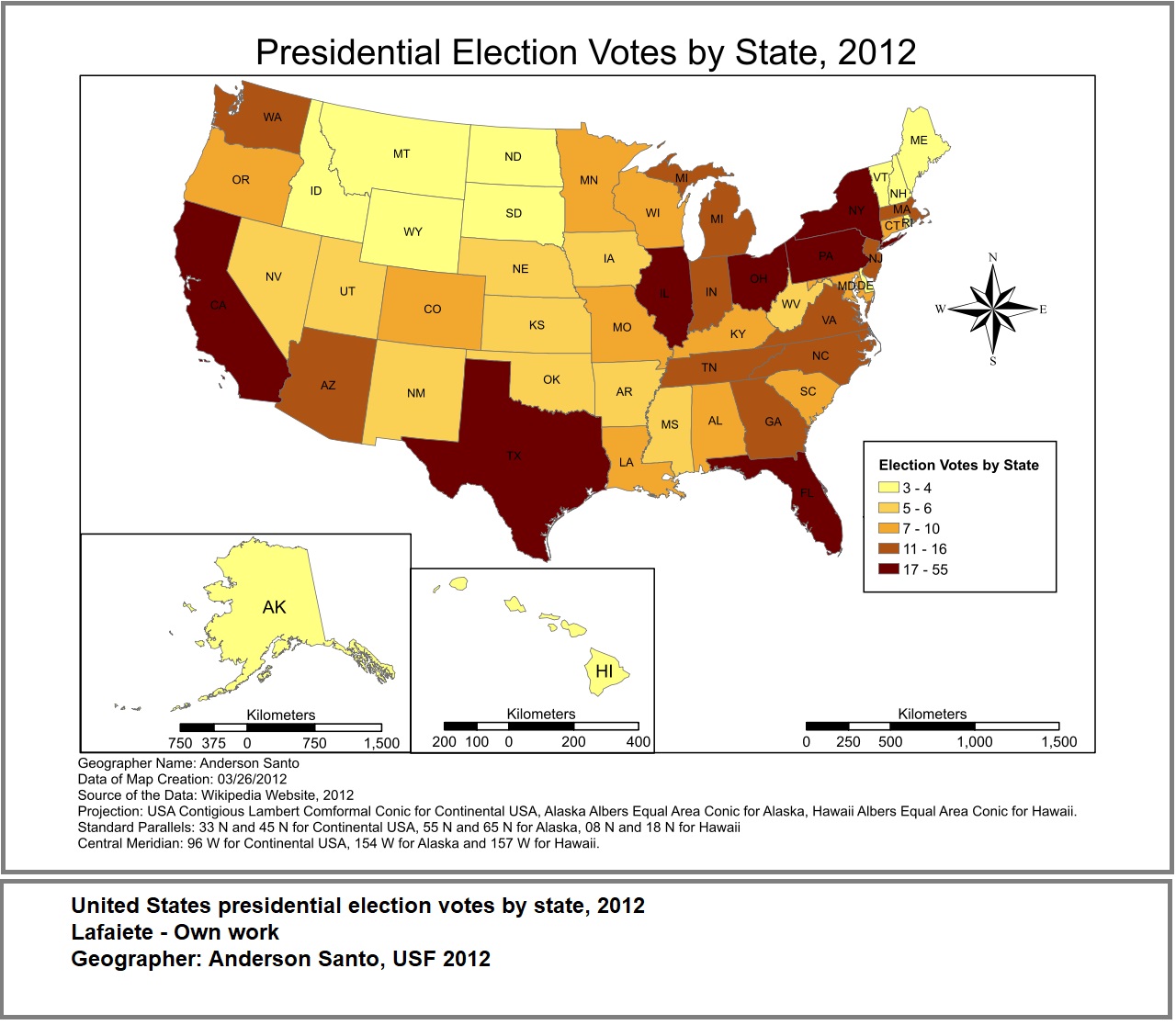

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution, empowers each state legislature to determine the manner by which the state's electors are chosen. The number of electors in each state is equal to the sum of the state's membership in the Senate and House of Representatives.

Currently, there are 100 senators and 435 state representatives. In addition, the Twenty-third Amendment, ratified in 1961, provides that the District established pursuant to Article I, Section 8 as the seat of the federal government (namely, District of Columbia) is entitled to the number it would have if it were a state, but in no case more than that of the least populous state. In practice, that results in Washington D.C. being entitled to 3 electors. U.S. territories are not entitled to any electors. There are currently 538 electors.

Following the national presidential election day (on the first Tuesday after November 1), each state counts its popular votes according to its laws to select the electors.

In 48 states and Washington, D.C., the winner of the plurality of the statewide vote receives all of that state's electors; in Maine and Nebraska, two electors are assigned in this manner and the remaining electors are allocated based on the plurality of votes in each congressional district. States generally require electors to pledge to vote for that state's winner; to avoid faithless electors, most states have adopted various laws to enforce the electors’ pledge.

The electors of each state meet in their respective state capital on the first Monday after the second Wednesday of December to cast their votes. The results are counted by Congress, where they are tabulated in the first week of January before a joint meeting of the Senate and House of Representatives, presided over by the vice president, as president of the Senate. Should a majority of votes not be cast for a candidate, the House turns itself into a presidential election session, where one vote is assigned to each of the fifty states. Similarly, the Senate is responsible for electing the vice president, with each senator having one vote. The elected president and vice president are inaugurated on January 20.

Even though the aggregate national popular vote is calculated by state officials, media organizations, and the Federal Election Commission, the people only indirectly elect the president. The president and vice president of the United States are elected by the Electoral College, which consists of 538 electors from the fifty states and Washington, D.C. Electors are selected state-by-state, as determined by the laws of each state. Since the election of 1824, the majority of states have chosen their presidential electors based on winner-take-all results in the statewide popular vote on Election Day. As of 2020, Maine and Nebraska are exceptions as both use the congressional district method; Maine since 1972 and in Nebraska since 1996. In most states, the popular vote ballots list the names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates (who run on a ticket). The slate of electors that represent the winning ticket will vote for those two offices. Electors are nominated by a party and pledged to vote for their party's candidate.[ Many states require an elector to vote for the candidate to which the elector is pledged, and most electors do regardless, but some "faithless electors" have voted for other candidates or refrained from voting.

A candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the presidency or the vice presidency. If no candidate receives a majority in the election for president or vice president, the election is determined via a contingency procedure established by the Twelfth Amendment. In such a situation, the House chooses one of the top three presidential electoral vote winners as the president, while the Senate chooses one of the top two vice presidential electoral vote winners as vice president.

The Electoral College never meets as one body. Electors meet in their respective state capitals (electors for the District of Columbia meet within the District) on the Monday after the second Wednesday in December, at which time they cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for president and vice president.

Although procedures in each state vary slightly, the electors generally follow a similar series of steps, and the Congress has constitutional authority to regulate the procedures the states follow. The meeting is opened by the election certification official – often that state's secretary of state or equivalent — who reads the Certificate of Ascertainment. This document sets forth who was chosen to cast the electoral votes. The attendance of the electors is taken and any vacancies are noted in writing. The next step is the selection of a president or chairman of the meeting, sometimes also with a vice chairman. The electors sometimes choose a secretary, often not himself an elector, to take the minutes of the meeting. In many states, political officials give short speeches at this point in the proceedings.

When the time for balloting arrives, the electors choose one or two people to act as tellers. Some states provide for the placing in nomination of a candidate to receive the electoral votes (the candidate for president of the political party of the electors). Each elector submits a written ballot with the name of a candidate for president. Ballot formats vary between the states: in New Jersey for example, the electors cast ballots by checking the name of the candidate on a pre-printed card; in North Carolina, the electors write the name of the candidate on a blank card. The tellers count the ballots and announce the result. The next step is the casting of the vote for vice president, which follows a similar pattern.

Under the Electoral Count Act (updated and codified in 3 U.S.C. § 9), each state's electors must complete six Certificates of Vote. Each Certificate of Vote must be signed by all of the electors and a Certificate of Ascertainment must be attached to each of the Certificates of Vote. Each Certificate of Vote must include the names of those who received an electoral vote for either the office of president or of vice president. The electors certify the Certificates of Vote, and copies of the Certificates are then sent in the following fashion:

• One is sent by registered mail to the President of the Senate (who usually is the incumbent vice president of the United States);

• Two are sent by registered mail to the Archivist of the United States;

• Two are sent to the state's Secretary of State; and

• One is sent to the chief judge of the United States district court where those electors met.

A staff member of the President of the Senate collects the Certificates of Vote as they arrive and prepares them for the joint session of the Congress. The Certificates are arranged – unopened – in alphabetical order and placed in two special mahogany boxes. Alabama through Missouri (including the District of Columbia) are placed in one box and Montana through Wyoming are placed in the other box. Before 1950, the Secretary of State's office oversaw the certifications, but since then the Office of Federal Register in the Archivist's office reviews them to make sure the documents sent to the archive and Congress match and that all formalities have been followed, sometimes requiring states to correct the documents.

Main article: Faithless elector

An elector votes for each office, but at least one of these votes (president or vice president) must be cast for a person who is not a resident of the same state as that elector. A "faithless elector" is one who does not cast an electoral vote for the candidate of the party for whom that elector pledged to vote. Thirty-three states plus the District of Columbia have laws against faithless electors, which were first enforced after the 2016 election, where ten electors voted or attempted to vote contrary to their pledges. Faithless electors have never changed the outcome of a U.S. election for president. Altogether, 23,529 electors have taken part in the Electoral College as of the 2016 election; only 165 electors have cast votes for someone other than their party's nominee. Of that group, 71 did so because the nominee had died – 63 Democratic Party electors in 1872, when presidential nominee Horace Greeley died; and eight Republican Party electors in 1912, when vice presidential nominee James S. Sherman died.

While faithless electors have never changed the outcome of any presidential election, there are two occasions where the vice presidential election has been influenced by faithless electors:

In the 1796 election, 18 electors pledged to the Federalist Party ticket cast their first vote as pledged for John Adams, electing him president, but did not cast their second vote for his running mate Thomas Pinckney. As a result, Adams attained 71 electoral votes, Jefferson received 68, and Pinckney received 59, meaning Jefferson, rather than Pinckney, became vice president.

In the 1836 election, Virginia's 23 electors, who were pledged to Richard Mentor Johnson, voted instead for former U.S. Senator William Smith, which left Johnson one vote short of the majority needed to be elected. In accordance with the Twelfth Amendment, a contingent election was held in the Senate between the top two receivers of electoral votes, Johnson and Francis Granger, for vice president, with Johnson being elected on the first ballot.

Some constitutional scholars argued that state restrictions would be struck down if challenged based on Article II and the Twelfth Amendment. However, the United States Supreme Court has consistently ruled that state restrictions are allowed under the Constitution. In Ray v. Blair, 343 U.S. 214 (1952), the Court ruled in favor of state laws requiring electors to pledge to vote for the winning candidate, as well as removing electors who refuse to pledge. As stated in the ruling, electors are acting as a functionary of the state, not the federal government. In Chiafalo v. Washington, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), and a related case, the Court held that electors must vote in accord with their state's laws. Faithless electors also may face censure from their political party, as they are usually chosen based on their perceived party loyalty.

|